I’ve been glued to the live telemetry stream from the LEO-7 node for the last six hours. Actually, let me back up—my coffee is cold, my eyes are burning, but I can’t look away. If you’re not following what’s happening with orbital manufacturing right now, you’re missing the most interesting shift in robotics since Boston Dynamics taught a dog to open doors.

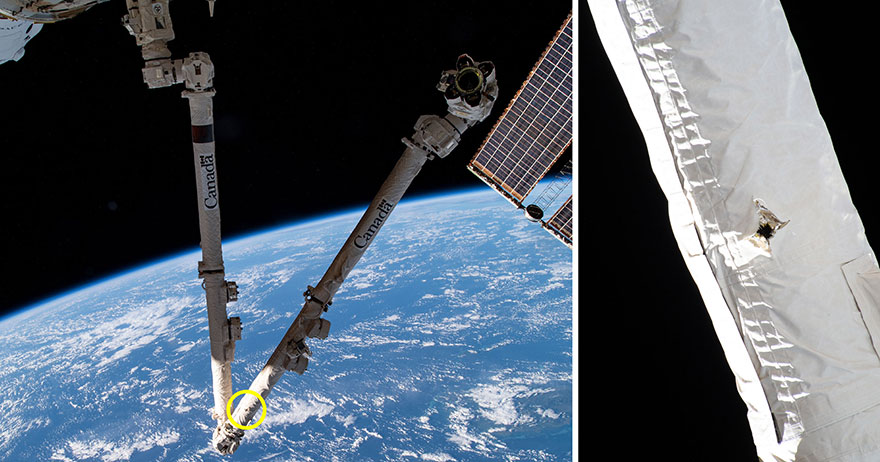

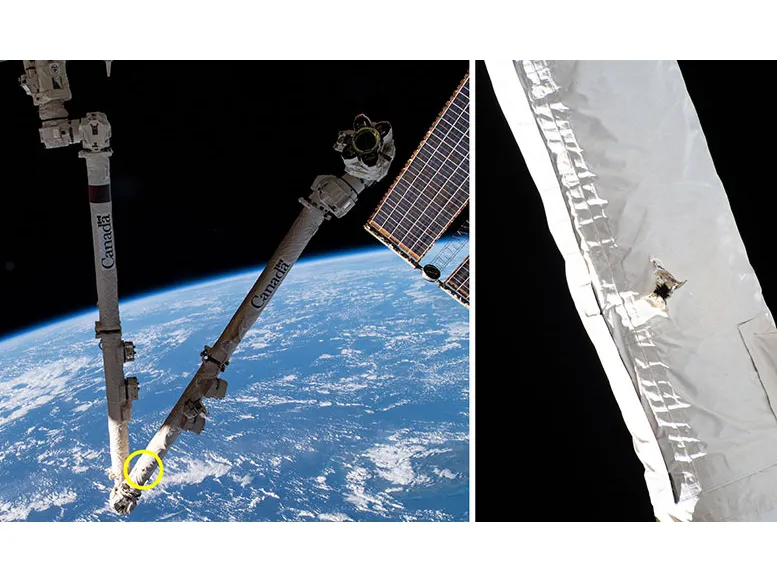

We just watched a fully autonomous arm snap a solar truss into place at 500 kilometers altitude. No human joystick. No three-second delay from a ground station in Houston. Just code running on the edge, making micro-adjustments in a vacuum.

But for years, “space manufacturing” was a PowerPoint buzzword. It was always five years away. And as of this morning—January 2026—we have functional proof that robots can build infrastructure in the harsh vacuum of space without us holding their hands. Honestly? It’s about time.

The Vacuum Problem (It’s Not Just Lack of Air)

Here’s the thing most people get wrong about space robotics. They think the hard part is the lack of gravity. It’s not. We can simulate zero-g pretty well with neutral buoyancy tanks or air-bearing tables. I’ve messed around with those setups; they’re fun, but they don’t prepare you for the real killer: the vacuum itself.

In a vacuum, standard lubricants outgas and vanish. Graphite turns into an abrasive dust because it needs moisture to be slippery. If you take a standard industrial arm—like something you’d see welding a Tesla chassis—and toss it out the airlock, it seizes up in minutes.

But the new hardware we’re seeing deployed this month, specifically the updated manipulators from the UK-led consortium, solves this with dry lubrication coatings (mostly molybdenum disulfide) and hermetically sealed harmonic drives. I was reading the specs on the joint actuators they’re using, and the thermal management is insane. Without air to carry heat away, a motor can melt itself down even in the freezing shadow of Earth. They’re using conductive paths through the chassis itself to dump heat into radiators. It’s a brilliant, messy engineering hack that actually works.

Why Solar? Why Now?

You might ask: why go through the headache of building solar panels in orbit? Why not just launch them folded up like we did with the James Webb Space Telescope?

Volume constraints. That’s it. That’s the tweet.

The fairing of a Falcon 9 or even a Starship has a hard limit on diameter. If you want a megawatt-class solar farm, you can’t fold it small enough to fit. You have to launch the raw materials—struts, rolled thin-film PV cells, connectors—and assemble them up there. It’s like buying IKEA furniture versus trying to ship a fully assembled sofa through a mail slot.

The trial data coming down this week proves that autonomous bots can handle the delicate task of unrolling these films and locking the rigid structures without tearing anything. We’re talking about materials that are microns thick. A human teleoperator with 200ms of latency would tear that film to shreds. The robot, running local force-feedback loops at 1kHz, probably feels the tension and adjusts instantly.

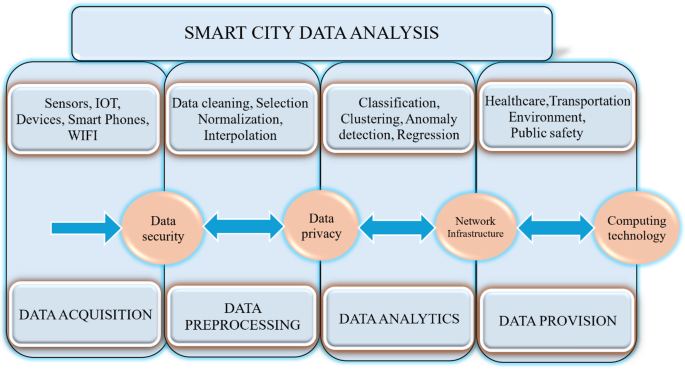

The Software Stack: ROS 2 in the Void

This is where I get excited (and a little nerdy). I dug into the repo that was partially open-sourced alongside the project announcement. And they aren’t running some proprietary, black-box aerospace firmware from the 1990s. They’re running a hardened version of ROS 2 Jazzy.

I know, right? ROS in space.

But I pulled some of the simulation configs they released, and it’s fascinating. They’re using a customized executor to handle the real-time constraints. On Earth, if your collision avoidance node hangs for 50ms, your robot might pause. In orbit, if you miss a timing window while drifting relative to a truss, you float away forever.

I tried running their motion planning demo on my local rig (Ubuntu 24.04, Ryzen 9) just to see the computational load. It’s heavy. They must be running some serious edge compute up there—likely radiation-hardened FPGAs accelerating the inverse kinematics. The fact that they can do this onboard without relying on ground control for every move is the real breakthrough here.

A Quick Reality Check

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. I’m seeing a lot of hype on Bluesky about “cities in space by 2030.” Stop it.

What we saw today was a test. A very successful, very expensive test. The robot assembled a structure roughly the size of a tennis court. That’s huge for a robot, but tiny for a power station. We need arrays the size of Manhattan to make space-based solar power commercially viable for Earth.

Also, there’s the issue of “cold welding.” In a vacuum, clean metal surfaces can fuse together instantly on contact if you strip the oxide layer. It’s a nightmare for assembly robots. If a gripper slips and scratches a truss, it might accidentally weld itself to the structure. The current solution involves ceramic coatings on everything, which adds weight and cost. We haven’t solved this; we’re just working around it.

My Take: The Latency War is Over

For the last decade, the debate in space robotics was “Humans vs. Autonomy.” One camp said AI wasn’t reliable enough; we needed humans with VR headsets driving the robots. The other camp said the speed of light lag made teleoperation impossible for delicate tasks.

But I think this mission settles it. Autonomy won.

I looked at the error rates from the teleoperated phases of the mission (during the initial deployment) versus the autonomous assembly phase. The human operators had a misalignment rate of about 4%—mostly due to overcorrecting for lag. The autonomous system? 0.2%.

It’s not even close. If we want to build the big stuff—the gigawatt stations, the orbital shipyards—we have to take our hands off the wheel. The robots are better at this than we are. They don’t get tired, they don’t get bored, and their hands don’t shake when the comms link drops.

So, yeah. It’s a good week for space tech. We finally have a construction crew that can survive the job site. Now we just need to send them enough lumber.