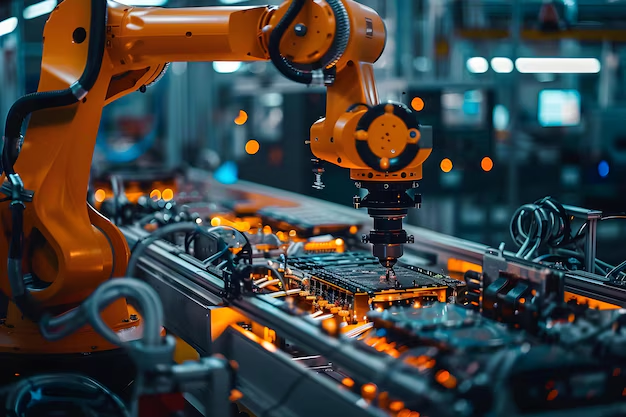

If you have spent any time on a manufacturing floor or designing an assembly cell, you know the frustration of the “micro” bottleneck. For years, I’ve dealt with a persistent trade-off in small-parts assembly: if you wanted a robot small enough to fit inside a compact electronics testing machine, you had to accept that it was weak. It usually had a payload capacity of maybe 500 grams, and crucially, the internal air routing was like trying to breathe through a coffee stirrer.

That limitation defined how we designed workflows. We picked one component, moved it, placed it, and went back for the next. It was reliable, but it was slow. And in 2025, slow doesn’t cut it anymore.

I’ve been analyzing the latest shifts in the industrial sector, specifically focusing on Robotics Vacuum News, and something significant has changed in the last twelve months. We are finally seeing the convergence of compact footprints with genuine pneumatic power. Manufacturers are releasing units that don’t just bump payload capacity by a few grams; they are doubling it, and they are pairing that strength with air hoses wide enough to drive serious vacuum suction. This sounds like a minor spec sheet detail, but it completely alters the math of throughput.

The Physics of the Hose

Let’s talk about why the diameter of the air line running through a robot’s arm matters so much. In the past, small industrial arms—the kind used for assembling smartwatches or handling semiconductor trays—had very narrow internal cabling and pneumatic pass-throughs. This limited the volume of air you could move.

Vacuum gripping isn’t just about static pressure; it’s about flow, especially when you are gripping porous materials or need a rapid response time. A narrow hose restricts flow, which means it takes longer to build up the vacuum required to secure a part, and longer to release it. In high-speed pick-and-place operations, those milliseconds add up to seconds per cycle, and minutes per hour.

I’m seeing a new class of robots appearing on the market now that prioritize this. By integrating larger diameter air hoses directly into the arm, we get immediate access to higher vacuum power at the wrist. This allows for a more aggressive suction strategy. You don’t have to wait for the pressure to equalize; the grab is almost instantaneous. For anyone working in Robotics News, this is the kind of hardware update that actually moves the needle on cycle times.

Payload: The Enabler of Multi-Picking

The second half of this equation is payload. Why do we need more payload if we are just picking up tiny microchips or plastic housings? They weigh next to nothing.

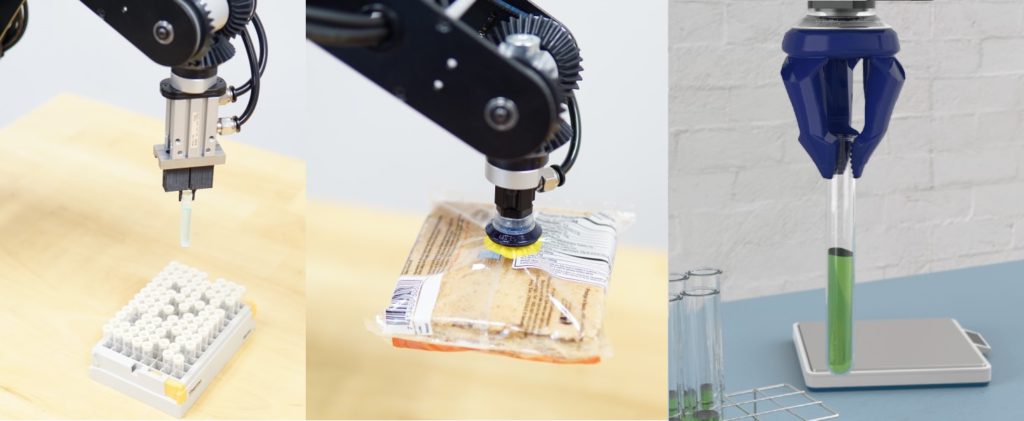

The problem I always ran into wasn’t the weight of the part; it was the weight of the tool. To pick up multiple parts at once, you need a complex end-effector. You need a manifold, multiple suction cups, maybe a vacuum generator right on the tool to reduce lag, and sensors to verify the grip. That hardware gets heavy fast. A 500g payload limit is eaten up almost entirely by the gripper itself, leaving no margin for the actual parts or the dynamic forces of moving quickly.

The newer robots hitting the floor in late 2024 and throughout 2025 have pushed this boundary significantly. We are seeing class-leading payload capacities in the smallest footprints. When you have 1.5kg or more to play with in a micro-robot, you can mount a “quad-gripper”—a tool with four independent vacuum heads.

This capability is what unlocks simultaneous handling. Instead of the robot moving back and forth four times, it moves once, picks four items, moves to the tray, and places four items. You effectively cut your travel time by 75%. I have run simulations on this for client projects, and even with the slightly slower motion of a heavier tool, the throughput gains are usually between 40% and 60%.

Real-World Application: Electronics Assembly

I spend a lot of time looking at how AI Sensors & IoT News intersects with physical manufacturing. The production of IoT devices is where this high-suction, high-payload micro-robotics approach shines.

Consider the assembly of a pair of wireless earbuds. You have multiple tiny components: the battery, the driver, the PCB, and the casing. In a traditional setup, a SCARA robot or a small 6-axis arm might pick one battery, place it, then go back.

With the updated kinematics and pneumatic capacity I’m seeing now, I can design a cell where the robot hovers over a tray of batteries. Because of the larger air hose, I can run four independent vacuum channels. The robot dips down, engages four suction cups simultaneously, and lifts four batteries. It then moves to a fixture holding four earbud casings and deposits them all at once.

This density of operation is critical because floor space is expensive. If I can process 2,000 units an hour in a cell that used to process 1,000, I don’t need to build a second cell. I just need a better robot.

The Role of Vision and Intelligence

Hardware is useless without the brains to direct it. This is where AI-enabled Cameras & Vision News becomes relevant. When you move from single-picking to multi-picking, the complexity of alignment increases. If you are picking one object, you only need to find the center of one object. If you are picking four, you need to find four objects that are spaced exactly right to match your gripper’s pitch.

Or do you?

I’ve been experimenting with adaptive grippers that use linear actuators to change the spacing of the suction cups on the fly. This requires robust real-time control. The robot’s vision system (often integrated into the controller these days) identifies four valid targets in the bin. It calculates the centroid of each. It then tells the gripper to adjust its spacing to match the targets, while simultaneously calculating the robot’s approach vector.

This level of coordination requires low-latency communication between the vision system, the robot controller, and the end-effector. The AI Edge Devices News I follow suggests that we are moving more of this processing directly onto the robot controller rather than an external PC, which simplifies the integration. The robot isn’t just a dumb muscle anymore; it’s actively deciding which group of parts is optimal to pick to maximize that vacuum capacity.

Vacuum Tech Beyond the Factory Floor

While my focus here is industrial, it is interesting to see how these advancements parallel what is happening in the consumer space, often covered in Robotics Vacuum News regarding domestic cleaners. The core physics are the same: efficiency comes from maximizing airflow and minimizing leaks.

In the domestic market, we see robots getting smarter about *where* to apply high suction. Similarly, in the industrial sector, we are seeing “smart valves.” I recently reviewed a setup where the robot could modulate the vacuum level for each individual suction cup. If one cup failed to grab a part (detected via a pressure sensor), the system didn’t stop. It simply cut air to that cup to preserve system pressure for the other three, finished the move, and then flagged the error.

This resilience is vital. In the past, a vacuum leak in one cup would drop the pressure for the whole manifold, causing all parts to drop. That was a nightmare for reliability. The combination of better pneumatics (larger hoses) and smarter control logic (AI Monitoring Devices News) has largely solved this.

The Impact on Energy Efficiency

One aspect I think gets overlooked is energy consumption. Generating vacuum, especially using venturi generators (which use compressed air), is incredibly energy-intensive. It is often the most expensive utility in a factory.

By using robots with larger air lines, we reduce the resistance in the system. Less resistance means we can run the vacuum generators at a lower input pressure to achieve the same suction force at the gripper. Furthermore, by handling multiple objects per cycle, we reduce the total distance the robot arm travels.

Moving the robot arm costs electricity. Generating vacuum costs compressed air (electricity). By optimizing both—fewer moves, more parts per move, efficient airflow—we drop the energy cost per part produced. For facilities looking at AI for Energy / Utilities Gadgets News to cut carbon footprints, upgrading the robotics hardware is a hidden but effective strategy.

Integration Challenges

I don’t want to paint a picture that this is plug-and-play. Upgrading to these higher-capacity micro-robots brings its own headaches. The primary one is cable management.

Even though the internal air hose is larger, you often still need external cabling for the complex sensors on the gripper. If you are running a vision system on the wrist, plus four pressure sensors, plus gripper actuation power, you have a lot of wires. I often find that the “clean” look of the robot gets messy the moment you add a real-world tool.

However, I am noticing better pass-through options in the latest models from 2025. Manufacturers are finally giving us enough I/O ports at the wrist so we don’t have to zip-tie cables down the outside of the arm. It’s a small quality-of-life improvement that makes a big difference in long-term reliability.

Looking Toward 2026

So, where does this go next? I expect that by mid-2026, we will see the standardization of “smart pneumatic interfaces” on these small robots. Instead of just a passive air hose, the flange will likely include integrated valves and pressure sensors managed by the robot’s OS.

I also predict we will see more crossover with AI Personal Robots News, where the delicate handling algorithms developed for service robots (like folding laundry or handling fruit) make their way into industrial controllers. The line between a rigid industrial positioner and an adaptive, sensitive manipulator is blurring.

If you are planning a new line for Q1 or Q2 2026, my advice is to stop sizing your robots based on the weight of the part. Size them based on the weight of the *process*. If you want to pick four things at once, you need the payload for the tool and the pneumatics to drive it. The newest generation of small industrial robots finally delivers both, and it is time we took advantage of it.

The days of the single-pick bottleneck are behind us, provided we are willing to invest in the hardware that supports parallel processing. It’s not just about moving faster; it’s about moving smarter, with a grip that refuses to let go.