I remember the first time I tried to build a condition-based monitoring system for a client’s industrial water pumps. It was 2019. I was young, naive, and convinced that the solution to everything was “stream it to AWS and let the cloud figure it out.”

Spoiler: It didn’t work.

We burned through the cellular data budget in three days. The latency was terrible. And honestly? We were just sending gigabytes of noise. It turns out that streaming high-frequency vibration data at 20kHz continuously is a great way to make telecom companies rich and engineers miserable.

Fast forward to today—January 2026—and the landscape (ugh, hate that word, let’s say “situation”) has completely flipped. If you’re still pushing raw accelerometer data to a dashboard, you’re doing it wrong. I’ve spent the last few months messing around with the latest crop of development platforms—specifically the ones pairing robust MEMS sensors with dual-core microcontrollers like the PSoC 6—and I finally feel like the hardware has caught up to the promises marketing folks were making five years ago.

The Hardware Finally Makes Sense

For the longest time, “Edge AI” felt like a buzzword looking for a problem. You had these tiny microcontrollers that choked if you asked them to do basic floating-point math, let alone run a neural network inference. Or you had powerful gateways that were too expensive to slap on every single motor in a factory.

But recently, I’ve been working with kits that actually bridge this gap. Take the Analog Devices CN0549 platform. It’s not just a sensor; it’s a wide-bandwidth MEMS accelerometer that actually behaves like the expensive piezoelectric sensors I used to drool over but couldn’t afford. When you pair that with something like an Infineon PSoC 6, you suddenly have a setup that can handle the data acquisition and the number-crunching right there on the din rail.

Why does this matter? Because of the “garbage in, garbage out” rule. In the old days, I’d use cheap I2C accelerometers. They had a bandwidth of maybe 1-2 kHz if I was lucky. If a bearing fault was developing at a higher frequency harmonic, I’d miss it completely. The sensor was literally blind to the problem I was trying to solve.

Now, we have MEMS sensors with flat frequency responses pushing way past 10kHz. That means we can actually “hear” the machinery screaming before it breaks.

Processing at the Edge: My Workflow

Here is where I usually get into arguments with cloud architects. They love their data lakes. I prefer decisions.

When I’m monitoring a compressor now, I don’t want a graph of vibration over time. I want a red light that turns on when the bearings are shot. To get that without bankrupting the project on data fees, I run the signal processing locally.

It usually looks like this:

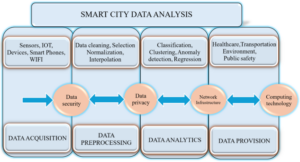

- Data Acquisition: The MCU wakes up, grabs a 1-second snapshot of vibration data at a high sample rate (say, 25.6 kS/s).

- DSP Filtering: I run a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) on the chip. This converts that messy time-domain waveform into frequency buckets.

- Inference: This is the cool part. I feed those frequency peaks into a tiny machine learning model running on the Cortex-M4 core.

- Output: The device sends a single byte: “Normal”, “Imbalance”, or “Bearing Fault”.

That single byte costs basically nothing to transmit. You can send it over LoRaWAN, NB-IoT, or even a flaky Wi-Fi connection, and it’ll get there.

The “Magic” of Anomaly Detection

I used to try to program thresholds manually. “If vibration > 2g, trigger alarm.”

Don’t do this. You will regret it.

Every pump vibrates differently. A pump mounted on concrete vibrates differently than the exact same pump mounted on a steel skid. If you hard-code thresholds, you’ll spend the rest of your life tuning them.

This is where the recent dev platforms shine. I can mount the sensor, put the machine in “learning mode” for an hour, and the onboard ML builds a baseline of what “normal” looks like for that specific machine. It’s using K-means clustering or a Gaussian Mixture Model (fancy math for “drawing a circle around the normal data points”) to define safety.

If the vibration drifts outside that circle? Boom. Anomaly detected.

I tried this recently on a pool pump I have in my backyard (my test bench is glamorous, I know). I loosened one of the mounting bolts to simulate a loose footing. The vibration amplitude didn’t change much overall, but the frequency signature shifted. A simple threshold would have missed it. The anomaly detection model flagged it in under ten seconds.

It’s Not All Sunshine and Rainbows

I don’t want to paint a picture that this is plug-and-play. It’s not. If you buy a dev kit today thinking you’ll have a deployed product tomorrow, you’re going to have a bad time.

Mounting is everything. I wasted three days last month debugging a “noisy sensor” that turned out to be a loose magnet mount. If the sensor isn’t mechanically coupled to the machine rigidly, you aren’t measuring the machine; you’re measuring the sensor rattling against the machine. I’ve started using epoxy or stud mounting for everything. Magnets are for fridge art, not industrial reliability.

Power consumption is tricky. Yes, the PSoC 6 is low power. But running DSP math and neural networks burns juice. If you’re running on batteries, you can’t infer every second. You have to duty cycle. I usually wake up every 10 minutes, listen for 5 seconds, process, and sleep. Balancing that duty cycle against the risk of missing a catastrophic failure is an art form.

Why I’m Finally Optimistic

Despite the headaches, I’m actually excited about where we are. In 2026, the barrier to entry has dropped through the floor. You don’t need a PhD in data science to train a model anymore—tools like Edge Impulse have democratized that. And you don’t need to design a custom PCB just to test a sensor—platforms like the CN0549 just plug into standard headers.

We’ve moved from “Can we do this?” to “How fast can we deploy this?”

If you’re an embedded engineer and you haven’t played with vibration analysis yet, grab one of these kits. Go stick it on your air conditioner, your washing machine, or your 3D printer. Break something on purpose. Watch the data change. It’s incredibly satisfying to see a microcontroller predict a failure before you can even hear it with your own ears.

Just please, for the love of all that is holy, stop sending the raw data to the cloud.