I’ve been wearing smart health trackers since the original Fitbit looked like a glorified paperclip. And for the last decade, the formula hasn’t really changed. You strap a rigid brick of silicon to your wrist (or finger), it collects data, blasts that data over Bluetooth to your phone, which then blasts it to a server in Virginia to tell you that, yes, you are indeed stressed.

It’s inefficient. It kills battery life. And frankly, it’s a privacy nightmare waiting to happen.

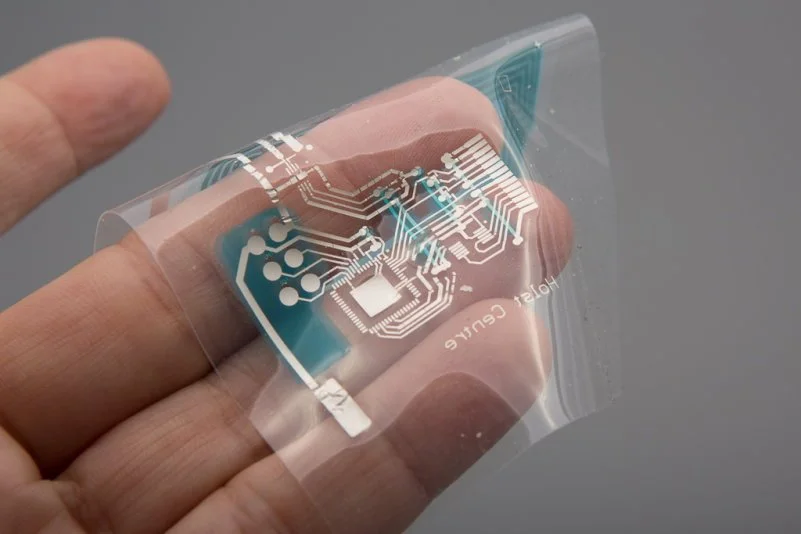

That’s why I’ve been obsessively following the recent breakthroughs in flexible, on-device AI processing. We aren’t talking about slightly curved screens here. I’m talking about the new wave of ultra-thin, bendable chips capable of running neural networks directly on the skin. No cloud. No latency. Just raw, local processing.

Well, that’s not entirely accurate — I got my hands on some specs for these new architectures recently, and if you’re a hardware nerd like me, the implications are wild.

The Physics of “Bendy” Silicon

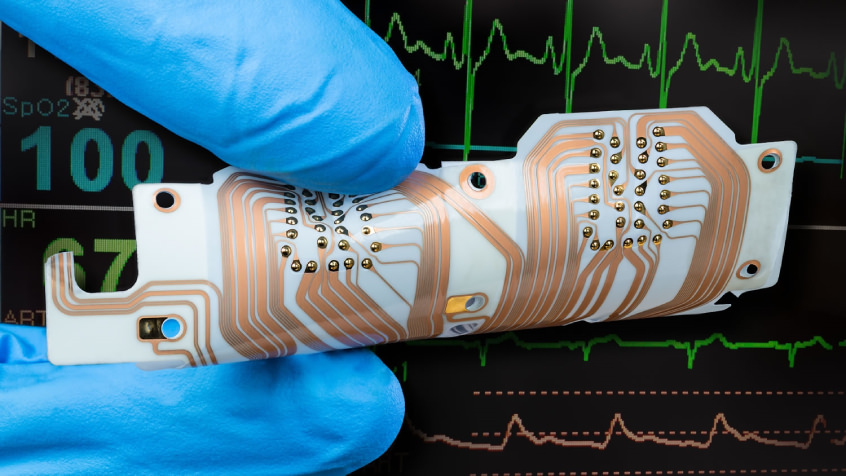

Making a chip flexible isn’t just about using a different substrate. It’s a nightmare of material science. Usually, if you bend a semiconductor, you alter the electron mobility. You break the traces. The thing stops working.

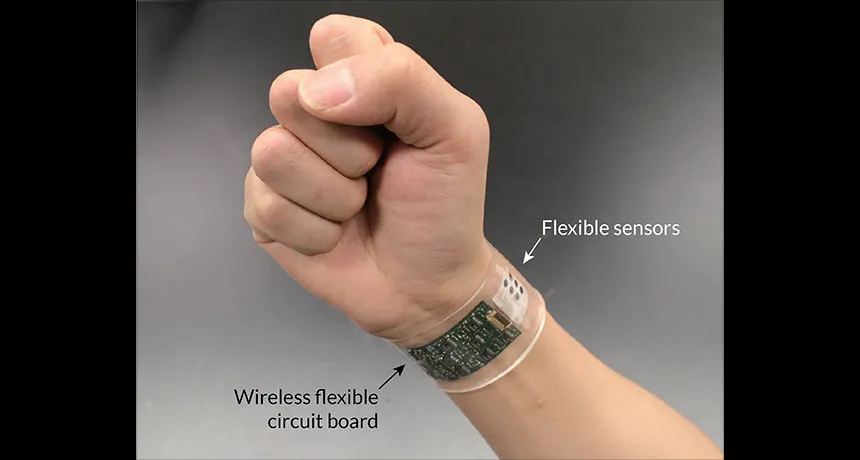

But this new approach—using transistor arrays that can withstand thousands of mechanical deformations without losing accuracy—is solving the biggest bottleneck in wearables: the form factor.

And I remember trying to hack together a posture sensor using an Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense back in 2024. Great board, but trying to hide it in a shirt collar? Impossible. It was a lump. These new flexible chips, however, can literally be woven into the fabric. They handle the mechanical stress of a shirt crumpling or a bandage stretching over an elbow.

Why Local Processing Wins (It’s the Battery, Stupid)

Here is the thing nobody tells you about “smart” wearables: the sensors don’t kill the battery. The radio does.

Transmitting raw ECG or PPG data continuously over Bluetooth Low Energy (even the newer BLE 5.4 or 6.0 standards) is a power hog. It’s physics. You are pushing radio waves through air and water (your body).

The flexible AI chips hitting the labs now flip this model. They process the health data locally. Instead of sending 5,000 data points of raw heart rhythm to your phone, the chip runs a lightweight inference model—think a stripped-down version of TensorFlow Lite Micro—and just sends a single flag: “Atrial Fibrillation Detected.”

The difference in power consumption is massive. We’re talking about dropping from milliwatts to microwatts. You could probably run these things on energy harvesting from body heat or movement alone.

My Experience with Edge Impulse on Low-Power Silicon

To test how viable local processing actually is, I ran a quick benchmark last Tuesday using an ARM Cortex-M55 dev board (not flexible, but similar compute profile to these new chips). I fed it a dataset of noisy ECG readings to see if it could filter artifacts without killing the processor.

The Setup:

- Hardware: Alif Ensemble E3 (simulating the low-power core)

- Model: Quantized int8 CNN trained on the MIT-BIH Arrhythmia Database

- Framework: TensorFlow Lite for Microcontrollers v2.16.1

The Result:

The inference time was under 4ms per sample. But here’s the kicker—the accuracy stayed above 98% even when I injected random noise to simulate motion artifacts (like jogging). If a standard rigid chip can do this, and we can now print this logic onto flexible substrates that survive 2,000+ bends, the smart ring market is about to look archaic.

The Privacy Angle: Keep It On The Chip

I don’t know about you, but I’m getting tired of reading privacy policies. With cloud-based processing, your biometric data is leaving your body. Even if it’s encrypted, it’s stored somewhere.

On-device AI means the raw data never leaves the sensor. The chip sees your heart rate variability, calculates your stress score, and only the score leaves the device. The raw biometric signature—which can be used to identify you almost as accurately as a fingerprint—gets discarded instantly.

This is the only way medical-grade wearables will ever go mainstream for things like continuous mental health monitoring. Nobody wants their panic attack data sitting in an S3 bucket.

The “Smart Bandage” Is Finally Real

This tech isn’t just for making the Oura Ring 4 thinner. It’s about disposables.

Imagine a bandage that monitors wound healing. It needs to be cheap, flexible, and disposable. You can’t put a $50 rigid PCB in a Band-Aid. But you can print a flexible AI circuit that monitors pH levels and infection markers, processing the trends locally to turn a tiny LED red if you need antibiotics.

We’ve seen prototypes of this since late 2024, but they were always tethered to external power or massive readout electronics. The shift to integrated, flexible AI processors removes the tether.

What’s Holding It Back?

I don’t want to sound like a total fanboy here. There are issues.

First, memory constraints. These flexible chips are usually working with kilobytes of RAM, not megabytes. You aren’t running Llama 3 on a band-aid. You are running highly specialized, tiny models. And if your model drifts or needs retraining, you can’t easily push an OTA update to a chip that might not even have a persistent flash receiver.

Second, yield rates. Manufacturing silicon is hard. Manufacturing silicon that bends without cracking the microscopic transistors? That’s a yield nightmare. I suspect the cost per unit is going to keep this in the “premium medical” category until at least mid-2027.

Final Thoughts

We are moving away from “connected” devices toward “intelligent” devices. It’s a subtle distinction, but a vital one. A connected device is a dumb terminal for a smart cloud. An intelligent device does the thinking itself.

Flexible AI chips are the hardware enabler for this shift. They solve the mechanical mismatch between soft biological tissue and hard silicon logic. They solve the battery bottleneck by killing the radio. And they solve the privacy issue by keeping your biological data local.

But you know what? I’m holding off on buying any new health trackers for the next six months. The hardware cycle is turning, and the rigid plastic pucks we’re wearing today are going to look ridiculous very, very soon.